(zk-learning) Deriving functional commitment families

Introduction

I just finished the second lecture of the Zero Knowledge Proofs MOOC titled Overview of Modern SNARK Constructions (yes I know, I’m two lectures behind schedule. Don’t remind me!!!).

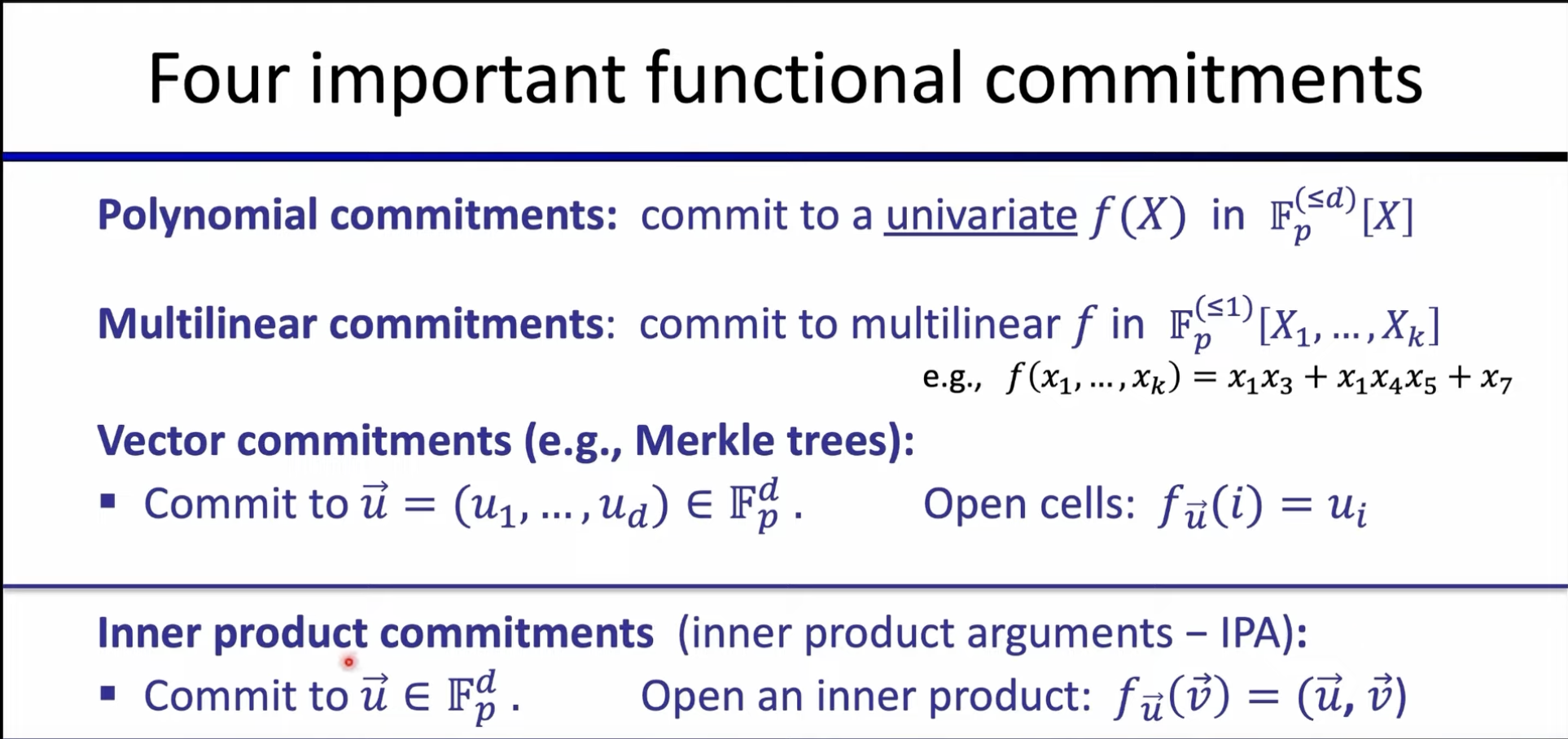

In the lecture Dr. Boneh introduces four important functional commitment families used for building SNARKs

- A univariate polynomial of at most degree $d$ such that we can open the committed polynomial at a point $x$.

- A Multilinear polynomial in $d$ variables such that we can open the committed polynomial at a point $x_1, …, x_d$.

- A vector $\vec{u}$ of size $d$ such that we can open the committed vector at element $u_i$.

- An inner products on vector $\vec{u}$ of size $d$ such that we can open the committed vector at the inner product of $\vec{u}$ and an input vector $\vec{v}$.

He mentions in passing that any one of these four function families can be built from any of the other four, but leaves it at that. I was left wondering… how?

Like a lot of things professors say, the details are left as an exercise to the reader ;). In this article I’d like to present a special case of that statement: given multlinear polynomials we can use it to build commitments for any of the other three families.

One by one let’s see how that’s done.

Univariate Polynomials

Recall the definition of a univariate polynomial commitment. We commit to a polynomial up to degree $d$ in a single variable $x$, and want to open it at arbitrary points.

One way to achieve this with a multilinear polynomial in $k$ variables is to “reduce” it to a single variable, and then map its coefficients to the coefficients in the unvariate polynomial.

Here’s what I mean.

The univariate polynomial is of the form

\[f(x) = a_0 + a_1x + ... \> + a_dx^d\]Now I’m going to be clever and write the multilinear polynomial as follows, collecting each sum of terms with the same number of variables under a single coefficient

\[F(X) = b_0 + b_1(x_0 + ... \> + x_d) + b_2(x_0x_1 + ... \> + x_{d-1}x_d) + ... \> + b_dx_1...x_d\]What if we substitute $x$ for every $x_i$ in the input vector $X$?

\[F(\begin{bmatrix}x_0 = x\\...\\x_d=x\end{bmatrix}) = b_0 + b_1(x + ... \> + x) + b_2(x + ... \> x) + ... + \> b_dx \\ = b_0 + \binom{d}{1}b_1x + \binom{d}{2}b_2x^2 + ... \> + \binom{d}{d}b_dx^2\]We’ve reduced it to a polynomial in a single variable! Now we can map the coefficients of $F$ to the coefficients of $f$

\[a_0 = b_0 \\ a_1 = \binom{d}{1}b_1 \Rightarrow b_1 = \frac{a_1}{\binom{d}{1}} \\ ...\]The general formula is

\[b_i = \frac{a_i}{\binom{d}{i}}\]Thus, committting $F$ with coefficients $b_i = \frac{a_i}{\binom{d}{i}}$ and opening it at $X = [x,…,x]$ is just like committing $f$ with coefficients $a_0, …, a_d$ and opening it at $x$.

Vectors

This one is easier than the previous one. In a vector commitment we commit to a vector $\vec{u}$ and open it at one of its elements: $f_{\vec{u}}(i) = u_i$.

We can implement this with a simple multivariate polynomial of the form

\[F(X) = u_1x_1 + ... + u_dx_d\]For input $i$ to $f_{\vec{u}}$, we evaulate $F(X)$ such that $x_i = 1$ and $x_j = 0, j \neq i$ for every element in $X$.

I.e.

\[F(X) = u_1x_1 + ... + u_dx_d \Rightarrow \\ F(X) = 0u_1 + ... + 1u_i + ... + 0u_d \Rightarrow \\ F(X) = u_i\]Thus, committing to

\[F(X) = \sum_{i=1}^{d}{u_ix_i}\]and opening it at

\[X = \begin{bmatrix}x_0 = 0\\...\\x_i = 1\\..\\x_d=0\end{bmatrix}\]is equivalent to committing to $f_{\vec{u}}$ and opening at $i$.

Inner Products

In an inner product commitment we commit to a vector $\vec{u}$ and open it by evaluating its dot product with an input vector $\vec{v}: f_{\vec{u}}(\vec{v}) = \vec{u}\cdot\vec{v}$.

This one is very similar to the vector committment. The multivariate polynomial stays the same. But instead of evaluating it at a point where all but one $x_i$ is non-zero, we substitute $v_i = x_i$ for all $i$.

\[F(X) = u_1x_1 + ... + u_dx_d\]So

\[F(\vec{v}) = u_1v_1 + ... + u_dv_d = \vec{u}\cdot\vec{v}\]Thus, committing to $F(X) = \sum_{i=1}^{d}{u_ix_i}$

and opening it at

\[X = \begin{bmatrix}x_0 = u_0\\...\\x_i = u_i\\..\\x_d=u_d\end{bmatrix}\]is like comitting to $f_{\vec{u}}$ and opening it at $\vec{v}$

Conclusion

This was a bit of a tangent that didn’t actually deepen my understanding of the lecture material, but it was fun nonetheless! As someone who hasn’t touched math seriously for 5+ years, it’s fun to wipe the dust off my long forgotten skills (admittedly this isn’t that challenging as far as serious math goes).

Bonus - A (attempted) multiliner commitment from univariate commitments

In the Univariate Polynomials section I showed how to create a univariate commitment from a multilinear commitment. What about the other way around?

I tried to find a way to represent a multilinear commitment of a function in $d$ variables as a commitment of $d$ univariate polynomials of degree one. But the math is more complicated and the work is incomplete, hence why this is a bonus section.

We can write a general multilinear function of $d$ variables in the following way:

\[F(X) = c_0 + c_1x_1 + ... + c_dx_d + c_{d+1}x_1x_2 + ... + c_{?}x_1...x_d\]How many coefficients $c$ do we have in this form? For the terms in one $x$ variable we have $\binom{d}{1}$ possibilities. For the terms in two $x$ variable we have $\binom{d}{2}$ possibilities, and so on. The total number of coefficients is

\[\sum_{i=0}^d{\binom{d}{i}} = 2^d\]So given

\[F(X) = c_0 + c_1x_1 + ... + c_{2^d-1}x_1...x_d\]My idea is to write $d$ univariate polynomials of the form

\[f_1(x_1) = a_1 + b_1x_1 \\ ... \\ f_d(x_d) = a_d = b_dx_d \\\]And multiply them together to get the generic multilinear polynomial

\[\prod_{i=1}^d{f_i(x_i)}\]Once I’ve expanded that and collected the terms, I’ll have coefficients in terms of $a$ and $b$ variables. Then I can map those coefficients to the $c$ coefficients and solve for the $a$’s and $b$’s.

If the multilinear polynomial is the product of the univariate polynomials, then comitting to the univariate polynomials is kind of like to comitting to the multivariate ones, right? I’m honestly not sure. This is where my math knowledge breaks down. Nevertheless, let’s move forward with this approach. I need to introduce some notation for the expansion formula.

Let $N_d$ be the set of numbers ${1, 2, …, d}$

Let $\binom{N_d}{i}$ be the set of combinations from choosing $i$ elements from $N_d$. E.g. $\binom{N_4}{2} = {{1, 2}, {1, 3}, {1, 4}, {2, 3}, {2, 4}, {3, 4}}$

Let $\sum_{a\in A}{f(a)}$ be a summation over the elements $a$ of a set $A$, applied to $f$.

My closed form expression is

\[\prod_{i=1}^d{f_i(x_i)} = \sum_{i=0}^d\Big(\sum_{a \in \binom{N_d}{i}}\big(\prod_{j \in a}a_j\big)\big(\prod_{k \in N_d - a}b_kx_k\big)\Big)\]Huh? I would be just as skeptical as you at this point. Don’t believe me? I’ll show you it works with an example. Let’s expand it for $d=3$.

When $i = 0$

\[i = 0 \Rightarrow \binom{N_3}{0} = \{\{\}\} \\ a = \{\}, k = N_3 - a = \{1, 2, 3\} \Rightarrow b_1b_2b_3x_1x_2x_3\]When $i = 1$

\[i = 1 \Rightarrow \binom{N_3}{1} = \{\{1\}, \{2\}, \{3\}\} \\ a = \{1\}, k = N_3 - a = \{2, 3\} \Rightarrow a_1b_2b_3x_2x_3 \\ a = \{2\}, k = N_3 - a = \{1, 3\} \Rightarrow a_2b_1b_3x_1x_3 \\ a = \{3\}, k = N_3 - a = \{1, 2\} \Rightarrow a_3b_1b_2x_1x_2\]When $i = 2$

\[i = 2 \Rightarrow \binom{N_3}{2} = \{\{1, 2\}, \{1, 3\}, \{2, 3\}\} \\ a = \{1, 2\}, k = N_3 - a = \{3\} \Rightarrow a_1a_2b_3x_3 \\ a = \{1, 3\}, k = N_3 - a = \{2\} \Rightarrow a_1a_3b_2x_2 \\ a = \{2, 3\}, k = N_3 - a = \{1\} \Rightarrow a_2a_3b_1x_1 \\\]When $i = 3$

\[i = 2 \Rightarrow \binom{N_3}{3} = \{\{1, 2, 3\}\} \\ a = \{1, 2, 3\}, k = N_3 - a = \{\} \Rightarrow a_1a_2a_3\]Putting it all together we get $2^d = 2^3 = 8$ terms, exactly as expected.

\[\prod_{i=1}^3{f_i(x_i)} = a_1a_2a_3 + a_2a_3b_1x_1 + a_1a_3b_2x_2 + a_1a_2b_3x_3 + a_3b_1b_2x_1x_2 + a_2b_1b_3x_1x_3 + a_1b_2b_3x_2x_3 + b_1b_2b_3x_1x_2x_3\]We can finally (maybe) figure out how to derive the $a$’s and $b$’s from the $c$’s. Let coefficient $c_B$ correspond to the term $\prod_{i \in B}{x_i}$ in the multilinear polynomial.

Then

\[B = N_d - a \Rightarrow a = N_d - B\]The $a$ in terms of $B$ is the start of our mapping, creating a system of equations for which we can solve for the $a$’s and $b$’s in terms of $c$’s. E.g. suppose $d = 3$ and $c_{{1, 2}} = 69$. In other words, our multilinear polynomial has the term $69x_1x_2$. Then we know $69 = a_3b_1b_2$.

If we did this for every $c$ then we’d have a non-linear system of equations. Now this is where I get skeptical. I vaguely recall from my university math courses that anything non-linear is extremely difficult to deal with, except in rare special cases. I think the approach breaks down with the system of equations.. so the bonus section ends here.

Congratualtions for reading until the end of this half baked stream of consciousness. If you’ve made it this far then please reach out. I guarantee we’ll have an interesting conversation.