(zk-learning) elaboration on the quadratic residue ZKP

Introduction

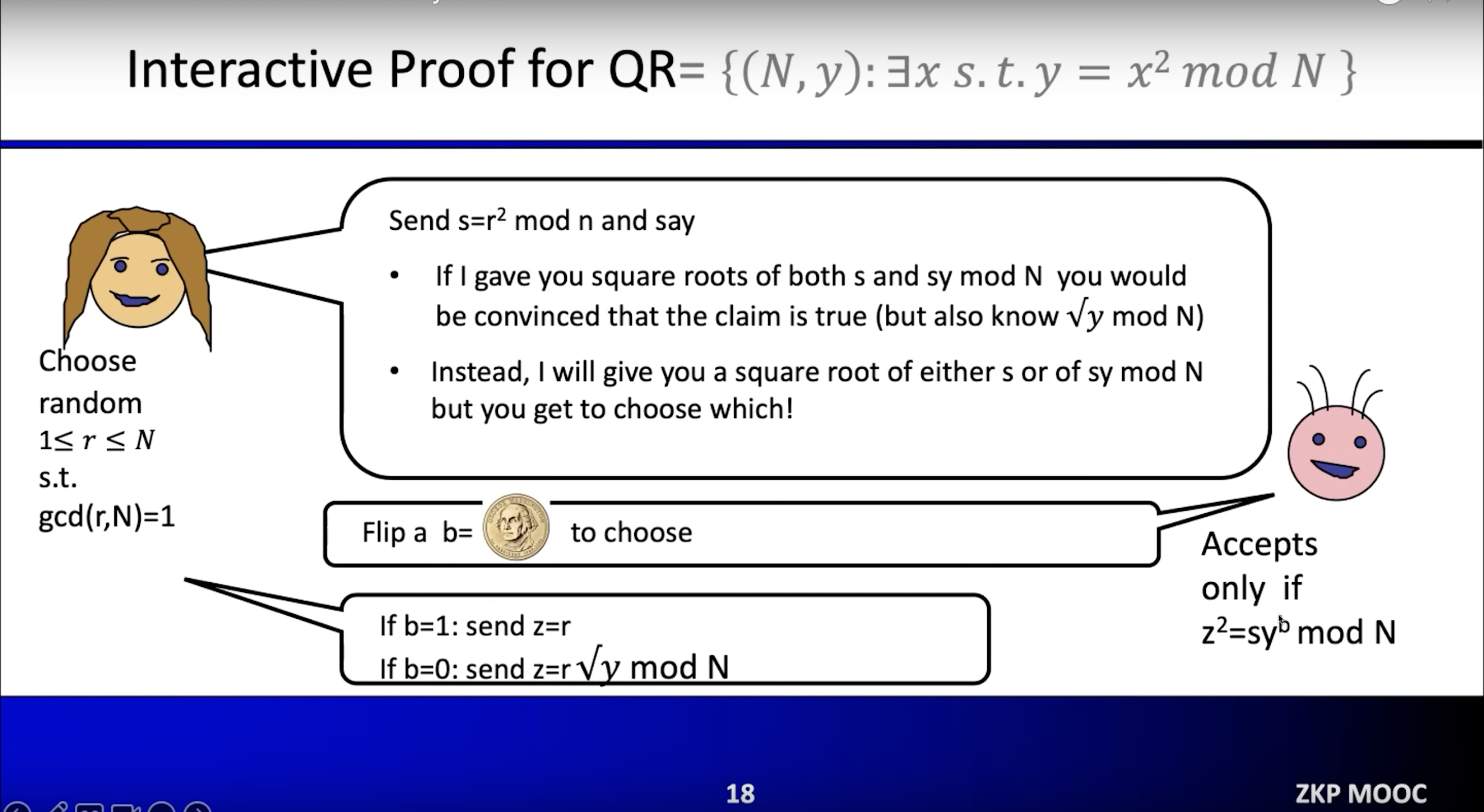

I just finished the first lecture of the Zero Knowledge Proofs MOOC titled Introduction and History of ZKP. The lecture described an interactive zero knowledge protocol to prove a number is a quadratic residue $mod > N$. In other words, a prover $P$ wants to convince a verifier $V$ that it knows $x$ such that $y = x^2 > mod > N$, without revealing $x$ to $V$. The variables $(y, N)$ are known to $P$ and $V$, but $x$ is only known to $P$.

The lecture did an excellent job explaining the protocol, but some parts weren’t explained explicitly. That was for brevity’s sake. Some parts are left for the viewers to think through themselves, and that’s a good thing. It allows more content to be packed into the lecture and forces the viewers to think more deeply about the subject.

In this article I’ll give a general description of zero knowledge interactive protocols that “clicked” for me, and then apply it to the quadratic residue example. I’ll make some facts about the protocol explicit that were left implicit in the lecture - only after I identified those implicit facts and made them explicit could I say with confidence that I understood why the protocol works. And I hope by the end of the article you’ll also better understand how that the protocol works.

If you’re reading this then I assume you’ve seen the first 30 minutes of the lecture (up to and including the Second example section).

General Description

Here’s my general description that I’m going to apply to the quadratic residue protocol:

In each iteration of the protocol, verifier $V$ asks the prover $P$ to perform one of two tasks $A$ or $B$, but ahead of time $P$ does not know which task it will be. $P$ and $V$ have agreed on these tasks before interaction starts.

The tasks are chosen such that if the claim is true (i.e. $P$ knows the secret), then $P$ can always perform both $A$ and $B$ correctly. But if the claim is false (i.e. $P$ doesn’t know the secret), then at best $P$ can only “fake” one of the tasks at the risk of not being able to perform the other.

If $V$ picks the task at random, then a $P$ who doesn’t know the secret has a 50% chance of faking the wrong task, and therefore being unable to perform the task chosen by $V$. After successive iterations the likelihood that $P$ doesn’t know the secret and correctly guesses which task to “fake” becomes increasingly small. After $n$ iterations, the likelihood that a $P$ who doesn’t know the secret guessed was able to guess the right task to fake $n$ times in a row is $\frac{1}{2^n}$.

As the likelihood that $P$ doesn’t know the secret decreases exponentially as $n$ increases, $V$ can be convinced that $P$ does in fact know the secret for sufficient $n$.

Before we apply my general description to the quadratic residue protocol, let me remind you of how the protocol works:

- $P$ chooses a random $r$ and sends $s=r^2 > mod > N$ to $V$.

- $V$ sends one bit $b$ back to $P$, and flips a coin to determine its value. If the coin lands heads then $b=1$. If the coin lands tails then $b=0$.

- $P$ receives $b$. If $b$ is 1 then it sends $z=r*x$ to $V$. If $b=0$ then it sends $z=r$ to $V$ (this is the opposite of what you see in the slides because the slides have a typo).

- $V$ receives $z$ and computes the expected value of $z^2$ using its knowledge of $s$ and $b$. If $b=1$ then the expected value for $z^2$ is $(r*x)^2 = r^2 * x^2 = s * y$. If $b=0$ then the expected value of $z^2$ is $(r)^2 = r^2$.

- $V$ rejects the proof if $z^2$ doesn’t match the expected value. If $z^2$ matches the expected value then $V$ either accepts the proof if it has been sufficiently convinced, or continues for more interations to increase its confidence in the proof.

What if $P$ doesn’t know the secret?

Let’s look at a scenario where $P$ does not know $x$ but tries to fake it.

$P$ fakes case $b=1$

Here’s how $P$ might convince $V$ in the $b=1$ case without actually knowing $x$.

- $P$ generates a random $r$, but instead of sending $s=r^2$ to $V$, it sends $s=\frac{r^2}{y}$

- $V$ sends $b=1$ to $P$

- $P$ sends $z=r$ to $V$.

- $V$ checks the expected value of $z^2$ against its actual value. The expected value for $z^2$ is $sy=y*r^2/y=r^2$ and the actual value for $z^2$ is $(r)^2=r^2$. The actual value matches the expected value, so $V$ is convinced.

What if $P$ guessed wrong and sent $s=\frac{r^2}{y}$ to $V$, but $V$ sent $b=0$ back? $P$ could send $z = r$ to $V$, but then $V$ would compute the expected value as $z^2 = s = \frac{r^2}{y}$ and the actual value sent by $P$ would be $z^2 = (r)^2 = r^2$, a mismatch! In fact, the only way $P$ could rectify the situation is if it actually knew $x$ and sent $z = \frac{r}{\sqrt{y}} = \frac{r}{x}$ to $V$.

As you can see, if $P$ doesn’t know $x$ and tries to “fake” the $b=1$ case, there’s a 50% chance $V$ sends $b=0$ and $P$ is unable to fulfill its role. Then $V$ can conclude that $P$ doesn’t know the secret $x$.

$P$ fakes case $b=0$

Here’s how $P$ could convince $V$ in the $b=0$ case without actually knowing $x$: $P$ can simply follow the original procedure. There’s nothing to “fake” because $P$ doesn’t need to know $x$ to compute a random $r$ and send $z=r$ to $V$.

But $P$ can still get caught by the $b=1$ case. If $b=1$, then $V$ expects to receive $z=r*x$, which $P$ cannot compute because it doesn’t know $x$.

What if P could predict the next $b$?

If $P$ knew $b$ in a given iteration before sending $s$ to $V$, then you saw in the previous sections how it could convince $V$ it knows $x$ without actually knowing $x$. Therefore, it’s critical that $P$ cannot predict $b$. Either the method by which $V$ selects $b$ must be hidden from $P$, or it must be selected with randomness. A fair coin flip was chosen for the protocol because it’s the simplest approach that satisfies those conditions.

What if P re-used $r$ between iterations?

$P$ should be careful to not re-use $r$ between iterations because that could accidentally give away the secret! Here is a scenario where $V$ could extract the secret if $P$ isn’t careful

- $P$ generates $r$ and sends $s = r^2$ to $V$.

- $V$ sends $b=0$ to $P$ and $P$ sends back $z_1=r$

- $V$ verifies $z_1^2 = s$ and continues to the next iteration

- $P$ uses the same $r$ and sends $s = r^2$ to $V$

- $V$ sends $b=1$ to $P$ and $P$ sends back $z_2=r*x$

- Now $V$ has both $z_1$ and $z_2$ and can compute the secret as $\frac{z_2}{z_1} = \frac{r*x}{r} = x$

What does the quadratic residue protocol achieve?

In the words of Professor Goldwasser, $P$ convinces $V$ not by proving the statement but by proving that it could prove the statement if it wanted to. I’m still trying to wrap my head around that one…

Conclusion

I hope this article made the quadratic residue example a bit less confusing. If, like me, this is your first foray into zero knowledge and your entire conception of what a proof is and what it means to prove something is upending, buckle up. I have a feeling it just gets more mind-blowing from here.

Where I’m going from here

I’d like to do another exercise based on the first lecture to deepen my understanding. The first example showed how to prove to a blind verifier that a piece of paper was made of two different colors. I’d like to apply the simulation paradigm to that example to formally show that it’s PZK (Perfect Zero Knowledge). Keep an eye out for that article.